Dion Horstmans is a giant in the art world – both in the physical sense and through his vigorous artwork which has graced everything from designer pads to Sculptures by the Sea and eighty-five metres of Melbourne’s Collins Square.

The Sydney-based artist and sculptor is far from slowing down though. By his own accord, if he wasn’t locked away in his Marrickville warehouse bringing his unique ideas to life six days a week, he’d be dead. “That’s all I know, that’s all I want. I’m going to be making s*** until the day I’m dead.”

This admission sets the precedence for not just the type of man Horstmans is, but also how his passion – which he calls his “mistress” – precedes just about everything in life.

Horstmans comes from the school of hard knocks and spent the formative years of his childhood living with his aunt and uncle on the tiny Cook Islands between New Zealand and Tahiti. His mother was a single parent who had him at a young age and his stepfather was abusive and left the family early on. This place that Horstmans describes as “not safe and not warm” was no environment for a child let alone a place to foster a lifetime of creativity. Somehow though, he still managed to pull it off. “I stuttered heaps, I was kind of scared a lot and looking for love. Because I stuttered and didn’t talk a lot, I’d sit in my room and make stuff or draw. I’d make architectural houses and playhouses for little soldiers.”

“I just wanted to make art. It was less of a career choice, more of a life choice.”

Growing up on the island, Horstmans was an easily distracted kid who skipped a lot of school. He’d instead spend his days frolicking the idyllic shores in a pair of shorts, chasing chickens and pigs, spear fishing, climbing coconut trees and building boats. This mischief would carry on into his teens as he worked as a car washer and rifled through customers’ glove boxes for spare change. At the same time he was also working as a gardener for his neighbour where he’d rifle through her rubbish bins to collect empty bottles for the local bottle shop. “I’d whip out to the back of the cornershop and take the same bottles I’d just given to the guy,” Horstmans laughs. “He’d give me another 4c a bottle which I spent on lollies.”

Even peddling ice cream didn’t escape the backdoor operations, with Horstmas following the trusty ‘one ice cream for the till, one ice cream for the pocket’ principle (There was also a special rule that if pretty girls walked in, they’d get free ice cream; if they had boyfriends he’d charge them double and take half the money). Hustling, it seems was in his blood. For Horstmans though, it was something more primal. It was simply about survival. “I was a young kid. We were dirt poor. Once you’re exposed to something, you want it,” he says.

Perched atop the roof of his Bondi apartment under the shade of a massive Moreton Bay fig this morning, Horstmans is far removed from his rougher days. Following his passion and not worrying about where he ended up has seemingly helped carve out his name and in turn the demand for his work across the country.

So what is the secret to successful art? “There’s no secret. It’s just balance. It’s the key to everything for me. Design is about balance. If there’s no balance within the piece, whether it’s a chair or a car, it won’t be user friendly.”

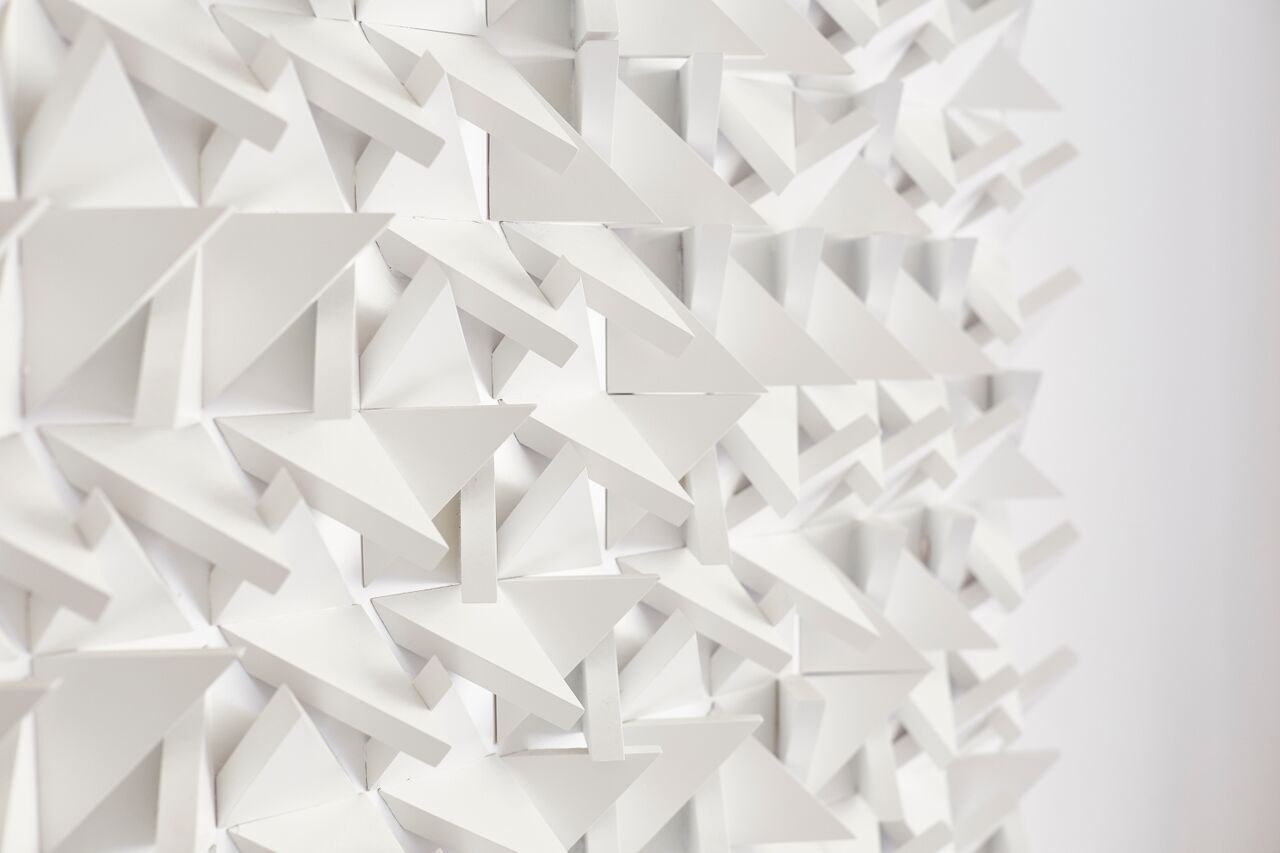

Art-wise, Horstmans believes it’s another thing altogether and it’s all subjective in that respect. Inspiration is usually a concoction of life experiences and the root of that for Horstmans forms the signature look of all his most sought after creations to date: the primitive arts teaming with geometric shapes and patterns. Growing up in New Zealand, the schools that Horstmans attended had many maraes (tribal meeting houses of Māori communities) which were adorned with patterns and lathe work finished in diamonds and triangles which were set in red, black and white. All of it was geometric and very repetitive regardless of whether it was on people’s clothes, the African beadwork or the New Guinean pottery.

Today Horstmans is taking what he knows best and playing with those shapes through metal elongation, shortening, flattening and stretching. The beauty lies in the organic detail and Horstmans seems to be especially proud of this. “I don’t use a computer. I just start and I do it all by hand in one go – Mr. Low-tech.”

He learnt the way of the old by simply doing what he craved and that involved a lot of drawing by hand. When he transitioned from building props for big budget films such as Mad Max and took on the life of a career artist, he didn’t even think of doing it for a living. As he explains, he did it because he “just wanted to make art. [It was] less of a career choice, more of a life choice.”

“Doctors told me I wasn’t going to walk again. And I was like, ‘Ok, cool. Thanks for that.”’

He would also soon experience first hand how difficult this chosen path of his would be. “A mate of mine left film and went out to be an artist and I said ‘F*** this, if he can do it so can I’ So I just left and never went back,” he admits. “It was tough in the beginning because of the transition from having constant income to near-nothing. I went on to work on props for Harley Davidson to Wonder White commercials – it didn’t matter.”

Regardless, it seems years of building a thick skin has meant that Horstmans can take on these rolling challenges without the slightest of hesitation. Where others would attempt the same path and quickly revert back to the comfort of civilian life with the slightest sign of trouble, art is still everything he’s ever believed in and it was never a case of if he was going to make it.

Where’s the proof? There’s about 106kg of muscle and a 6’ 6” frame behind it. Horstmans is a rather stocky guy and sculpting his physique has absolutely nothing to do with sculpting art. “I fell out of a high-rise while cleaning windows. I fell 15 metres, landed on my arse, smashed my pelvis, front and back both sides, smashed my elbow. My L1-L5 smashed, ruptured lung, ruptured kidney, spleen; I got pretty f***ed up.”

“Doctors told me I wasn’t going to walk again. And I was like, ‘Ok, cool. Thanks for that.”’

Horstmans went on to spend four and a half months in hospital on his back before moving onto a body brace for three months and then onto crutches and a walking stick. Recovery time for him to walk again unassisted took about a year. That entire time he was in hospital without the use of his legs was spent drawing with his hands. He continues training to this day to prevent his body from weakening and relapsing from those injuries.

It’s only fitting then that for a man who’s started with little and done it all, there’d be some sage advice for the budding artists out there. What does he have to say to the next generation of creatives?

“Just do it. Don’t f*** around. No one’s going to give you a hand out. Believe in your own ability and also have something outside of your art to do. Cook something different that is tangible. Being creative like that, it’s being in the unknown the whole time.”

In the end, the beauty of it all appears to be sustained and blissful self-indulgence. As Horstmans explains, he’s making art for him. He gets to do what he likes for nine hours a day, six days a week and he’s not making something someone else is telling him to make. “It’s ‘I like what you’re doing. Can I have a piece?'”

Photography produced exclusively for D’Marge by Peter Van Alphen – No reproduction without permission.

1/10

1/10

2/10

2/10

3/10

3/10

4/10

4/10

5/10

5/10

6/10

6/10

7/10

7/10

8/10

8/10

9/10

9/10

10/10

10/10