We’ve all heard the jokes from our hirsute mates. Something along the lines of, “You’re letting the side down,” or, “Cute face.” As any sane, 21st century man would, you probably wrote them off, confident enough in your clean-shaven charm not to submit to the fashion trend that pre-dates fashion. Plus: whenever you’ve tried to grow a beard you’ve never got past the “bum fluff” stage.

But however ugly your patchy sideburns, Henry J. Pratt, a New York hipster philosopher reckons the uglier moral sin is not to grow anything at all. In fact, his latest academic paper, “To Beard or Not to Beard: Ethical and Aesthetic Obligations and Facial Hair” was subject to serious discussion at the this month’s eastern division meeting of the American Philosophical Association in New York.

In a recent interview with Quartz, Pratt explains how, up until studying this topic, he had never considered the moral implications of growing a beard: “I’ve worn different beards, mustaches, sideburns, and so forth through the years, as well as being clean-shaven on occasion, but I can’t claim that any choices about that have to do with ethics.” However, as he began to play devils advocate with the premise of an 11th century philosopher, Saint Anselm of Canterbury, he was forced to reconsider.

Anselm believed: “Not having a beard is not dishonorable for a man who is not yet supposed to have a beard, but once he ought to have a beard, it is unbecoming for him not to have one. In the same way, not having justice is not a defect in a nature that is not obligated to have justice, but it is disgraceful for a nature that ought to have it.”

“To whatever degree his being supposed to have a beard shows his manly nature, to that degree his not having it disfigures his manly appearance.”

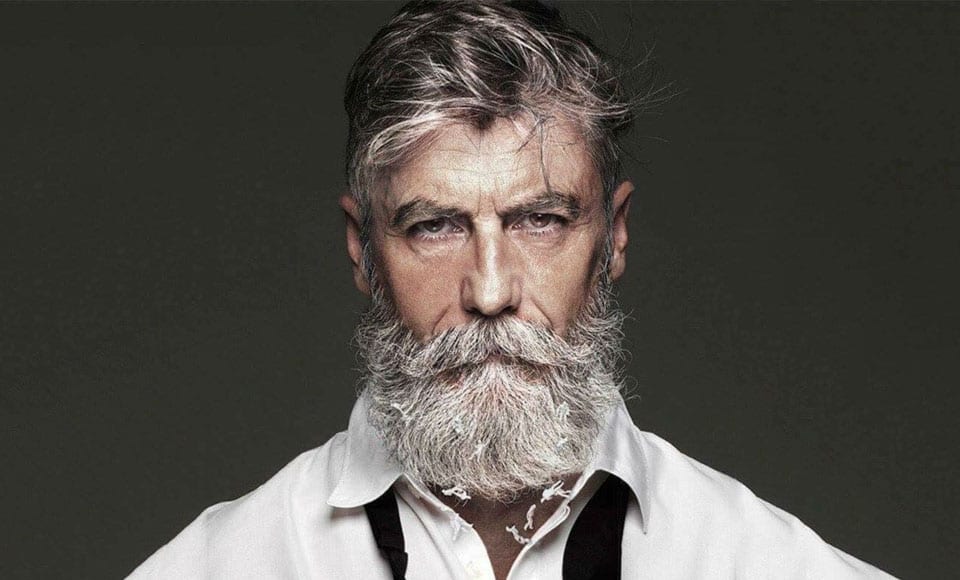

While Pratt admits this sounds “ridiculous,” he says rules of logic forced him to take Anselm’s position seriously, concluding that—if you believe beauty has moral worth—you have a responsibility to make the world better aesthetically: “We ought to respect the beautiful and create it where possible: if one can grow beautiful facial hair, one should, as it has moral worth. And given that one ought to be authentic to oneself, if that self (and the life story accompanies it) produces facial hair, then one has the aesthetical obligation to do so.”

When Quartz asked him where “growing a beard” stacks up alongside our other moral responsibilities, Pratt admitted that, from a consequentialist point of view, “Even if it’s good to create beauty, if it interferes with something else more important, it should be put aside… That said, if the costs are negligible—say, it’s way easier for me to grow a lavish beard than it is to shave every day—a consequentialist will say to go for it.”

“If I’m spending the time I should be reading to my kids on mustache waxing, that’s morally problematic, even if it’s a fine-looking mustache.”

While Pratt acknowledges that not all beards reach #majestic status, he cites the furry friends of Abraham Lincoln, Jesus, and Santa Claus, as examples of beards which “add aesthetic value to the world.”

But, having agreed with Anselm from the start point that “beauty has moral worth,” Pratt goes on to say that, from other points of view it makes less sense; facial hair has different connotations in different cultures, for example. In light of this, he concludes that there are (at least) five ways to address the ethics of facial hair:

- Take feminism seriously, reject the obligation to grow aesthetically pleasing facial hair in favor of the obligation to grow ugly facial hair, and abandon traditional moral theories.

- Reject feminist concerns about patriarchy, maintain a traditional moral theory, and accept the obligation to grow aesthetically pleasing facial hair.

- Keep a traditional moral theory, but find a way to argue that it does not entail the obligation to grow aesthetically pleasing facial hair. (Or, perhaps, claim that these obligations exist, but are so weak that they are almost always trumped by more significant considerations.)

- Reject the argument that there are obligations of one kind or another having to do with aesthetic properties, and conclude that there are no pogonotrophic [the act of cultivating facial hair] obligations.

- Strategically reframe facial hair as symbolic of something other than patriarchical power structures, e.g., by encouraging its growth by women and feminist men.